Important models that have been developed to better understand the process of PTG are The Functional Descriptive Model of Posttraumatic Growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995), The Model of Life Crises and Personal Growth (Schaefer & Moos, 1992), and the Conservation of Resources Theory (COR) (Hobfoll, 1989).

The Functional Descriptive Model of PTG (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995) (See Figure 1) proposed that the occurrence of PTG, rather than an outcome is an ongoing process of struggle with the new reality of trauma survivors’ life. The model emphasizes the crucial role of individuals’ personality characteristics, challenging conditions, management of the emotional distress, social influences, self-disclosure, and especially ruminations as part of the cognitive processing that was shattered by the traumatic event. Moreover, the model emphasizes that PTG is in a mutual interaction with life wisdom and the narrative development.

The traumatic events shatter the assumptive world of the individual. In order to cope with the distress that resulted from this challenge; cognitive processing is activated. This constructive cognitive processing works as the mechanism that aims to change schemas. Early responses to traumatic experiences are always automatic, in other words, they include intrusive ruminations. Since the distress caused by the traumatic event keeps the cognitive processing active; the process of schema change can take time. Tedeschi and Calhoun (1995) called this process as “grief work” because of the fact that the sense of loss, which is

related to trauma, is gradually accepted by the individual. With the contribution of the self-disclosure and social support, individual becomes more able to deliberately ruminate and to analyze the event and its consequences in an intentional way. Therefore, the schema change and posttraumatic growth can be achieved.

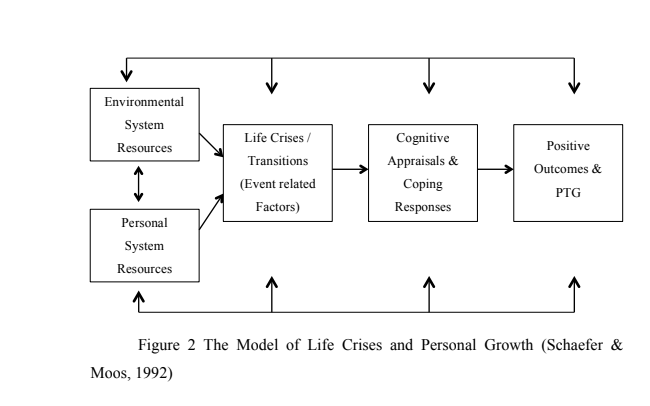

The Model of Life Crises and Personal Growth (See Figure 2) was developed by Schaefer and Moos (1992) in order to conceptualize the determinants of positive outcomes of life crises. With the aim of understanding

how individuals are positively adapted to life crises, the model emphasizes that it is crucial to work on the factors facilitating individuals’ maintenance of their healthy functioning and their own resources leading to posttraumatic growth in the aftermath of crises.

As the model proposed, personal and environmental system factors that are present before the event shape traumatic events and life crises. These traumatic event characteristics influence cognitive appraisal and coping responses. Moreover, coping and appraisals contribute to the development of personal growth or positive outcomes following life crises. Each stage of the model has an influence on all other stages; in other words, all parts of the model are connected with each other via feedback loops.

Personal system resources consist of socio-demographic characteristics such as marital status, gender, education level, and age, and personality characteristics.

Environmental system resources include financial status, and living conditions such as family environment and quality of life determinants.

Furthermore, perceived or objective severity, duration, and timing of the life crisis constitute the event related factors that represent life crisis and transition panel of the model.

In their model, Schaefer and Moos (1992) divided coping responses into two types namely, avoidance and approach coping. Individuals using avoidance coping tend to suppress the problem and they are unwilling to take action to change the situation and its possible emotional consequences. On the other hand, approach coping represents the reappraisal of the crisis and trying to actively analyze the event rationally and taking action to cope with it.

Therefore, The Model of Life Crises and Personal Growth (Schaefer & Moos, 1992) demonstrates that the occurrence of positive outcomes and PTG is determined by the combination of the individual’s personal and environmental resources, the factors related to the traumatic event and the type of appraisal and coping strategy.

In the literature, there is a growing debate on the illusory side of PTG. There are several studies focusing on the illusory side of growth following trauma (Taylor, 1983; Taylor & Aymor, 1996; Maercker & Zoellner, 2004; Zoellner & Maercker, 2006). It has been proposed that PTG might be related to the distorted positive illusions serving to decrease the distress level of individuals in the aftermath of trauma. The Janus Face Model was developed by Maercker and Zoellner (2004) in order to examine the components of growth following traumatic experience. These components were named as the constructive and illusory sides of PTG. Constructive side represents a positive adaptation to trauma and occurs when individuals effectively coped with the traumatic experience and its negative effects. Whereas, illusory side of PTG is a perception of growth that is not genuine and that serves to counter balance negative emotions following trauma that individual was unable to cope with. Furthermore, studies showed that there was a need for an action, in other words, a shift from growth cognitions to growth actions, in order to note a more constructive and permanent PTG following traumatic experience (Pat-Horenczyk & Brom, 2007; Hobfoll et al., 2007; Johnson, Hobfoll, Hall, Canetti-Nisim, Galea, & Palmieri, 2007).

The Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory (Hobfoll, 1989) is an integrative theory that focuses on both environmental and internal processes equally. In this theory, Hobfoll (1989) proposed that people are motivated to obtain, build and protect resources that are socially accepted and meaningful for them and that help them to cope with stress and survive. Hobfoll (2001) affirmed that stress could occur when individuals’ resources were threatened with loss; when they were actually lost; or when individuals failed to replenish resources after significant resource investment. The resources can be objects, personal characteristics, conditions, or energies (Hobfoll, 1989) and they are the necessity for understanding stress.

According to COR Theory (Hobfoll, 1989), it is important to focus on the effects of resource losses and gains following traumas. In this theory, there are three fundamental principles: the primacy of loss, resource investment, and loss and gain spirals.

The first principle is the primacy of resource loss, saying that resource loss is always more prominent than resource gain. The primacy of loss was explainedby individual’s giving more importance to negative information than positive information named as “negativity bias” (Hobfoll, 2001). The second principle is the resource investment. In this principle, it was suggested that: “people must invest resources in order to protect against resource loss, recover from losses, and gain resources”. Therefore, people with more resources are less vulnerable to resource loss and more capable of gaining resources; and those with fewer resources are more vulnerable to resource loss and less capable of gaining resources. Consistently, it was stated that individuals who were able to invest their resources more successfully, resisted negative impacts of traumatic stressors better than individuals who are lacking or misusing their resources (Freedy & Hobfoll, 1995). Individuals when they are under stressful conditions must use their resources in order to successfully cope with stress; however, resource reservoirs become depleted in traumatic stress due to the fact that in trauma, resource losses are abrupt, deep, and broad. Therefore, the loss cycle develops (Hobfoll, 2001). With greater resource loss, the level of distress increases because of the fact that individuals become less capable of responding to stress (Dekel & Hobfoll, 2007; Freedy & Hobfoll, 1995).

The third principle of COR Theory is loss and gain spirals. The initial loss makes individuals more vulnerable to further loss; therefore, when they face with secondary stressors, additional resource losses occur and each loss makes individual more vulnerable to psychological distress as resources are continuously depleted.

The Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory (Hobfoll, 1989) differs from other stress theories due to its emphasis on understanding the individual in terms of personal, social, and larger system resources rather than focusing only on individual psychology (Freedy & Hobfoll, 1995).

According to Hobfoll et al. (2007), action is an important element in the growth process. In the COR theory, it was proposed that the benefits of PTG were dependent on the transition from cognition to action which is called as “action based growth”. In order to report posttraumatic growth that embodies real positive adaptation, it is necessary that the action accompany the cognitions of individuals.

The findings of the research on 11 September 2001 and in Israel during the times of violence and terrorism revealed that PTG was significantly related to the high level of distress. Additionally, it was indicated that individuals exhibited PTG only if they translated their cognitions of growth to the growth actions (Hobfoll et al., 2007).

Recent Comments